The new Age of the Customer is upon marketers. Graphic credit: Forrester Research

The new Age of the Customer is upon marketers. Graphic credit: Forrester Research

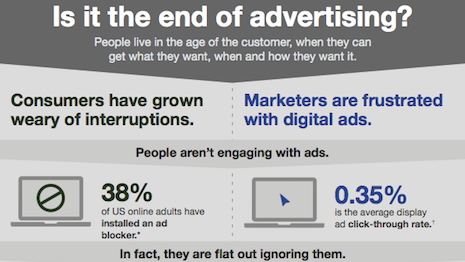

Forrester Research is calling the end of advertising as we know it, signaling the inevitable departure of interruption-based messages that drive hundreds of billions of dollars of revenue for publishers, ad platforms and vendors.

Driven largely by technology trends, antsy advertisers and weary consumers, advertising’s metamorphosis will lead to the rise of chatbots, voice agents and intelligent personal assistants that grow smarter with each consumer interaction.

“The era of the end of interruptions is dawning,” said James L. McQuivey, vice president and principal analyst at Cambridge, MA-based Forrester. “Every time advertising is growing and useful is because it’s a part of a conversation with the customers. It transcends the interruption-based model and becomes part of a conversation.

“We’re moving to a world where very few things you’re doing are interruptible,” he said.

Advertising shaped culture, delivered product information and bolstered the economy. New digital tools that often outperform advertising are causing the ad model to fray.

Advertising played four crucial economic and societal roles. Graphic credit: Forrester Research

Advertising played four crucial economic and societal roles. Graphic credit: Forrester Research

Rough ride

It is easy to surmise that Forrester’s stake-in-the-ground prediction marks the nadir of traditional, mass advertising.

“If advertising was the perfect expression of the world in which big companies and big governments transmitted monolithic messages to mass audiences, then the end of advertising signals the end of treating people as part of a monolith,” Mr. McQuivey said.

“We live in a culture of individuals who expect to be treated like individuals, which was not true in the days of the Marlboro Man,” he said.

An immediate casualty of this shift is the likely disappearance next year of $2.9 billion in display advertising, Forrester claims in its new report titled, “The end of advertising as we know it.”

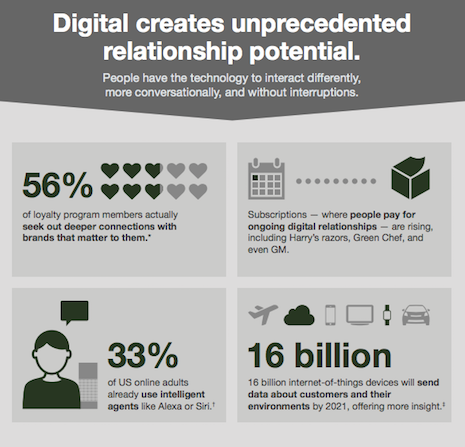

In that report, Mr. McQuivey and his coauthor, Keith Johnston, recommend that chief marketing officers should shift billions of dollars from ad interruptions to branded relationships that are intelligent and conversational.

Consumers are ready for deeper relationships with marketers that matter to them, the authors point out. Embedding personality in the brand’s current conversation is one of the clearest steps to take.

Of course, calling time on traditional advertising was not born of impulse.

CMOs from leading advertisers such as Procter & Gamble Co. have ratcheted up their criticism of the state of advertising. They take particular issue with the lack of measurement or the failure to effectively connect dots between ad spend and product sales.

“As advertising is coming under scrutiny, the consumer’s attention is wandering away to [Amazon’s personal assistant] Alexa,” Mr. McQuivey said.

“As both of these things happen at the same time, this weakening confidence in digital advertising coupled with a consumer interest in looking elsewhere such as Alexa to get their needs met, it raises the opportunity to question advertising, not just tweak it,” he said.

Ads are ignored, but stories connect. Graphic credit: Forrester Research

Ads are ignored, but stories connect. Graphic credit: Forrester Research

Talk is not cheap

Ironically, woes associated with traditional and digital advertising will renew interest in word-of-mouth marketing. The challenge is to rethink advertising and marketing as conversations with intelligent voice-based agents such as Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa, Google Home and Samsung’s own Bixby.

These agents will be artificially intelligent and constantly improving, with access to information and products that is current and pertinent to the consumer’s search or shopping needs.

“It means advertisers are going to find out very quickly whether their brands or products are suitable for a conversation,” Mr. McQuivey said. “Not every product will be, and this will be humbling for the brand.”

The changed advertising model threatens two other constituencies whose livelihoods depend on the old system of buying time and space for a fee or on performance: publishers and ad agencies.

Already leaching ad dollars to Facebook and Google, publishers now have to face a future where intelligent agents such as Amazon’s Alexa deliver and read aloud the news to consumers.

While the Internet’s arrival devastated print-dependent revenue models, and Facebook and Google’s usurpation of the gateway to news content split audience from media brand, the third wave is driven by artificial intelligence that learns and improves with repeated user interactions and recognition of repetitive behavior.

The question is, where does an advertiser fit into a voice-driven interface without interruption? Also, how can a media brand monetize this experience?

Mr. McQuivey sees a couple of paths.

One, publishers can develop their own voice agents. The Wall Street Journal, for example, might want to filter and deliver the news in its own authoritative voice that reflects the brand tone and line of reporting.

“Two things: one, I would pay for that and it would reinforce the subscriptions, and also, it gives the opportunity to say, ‘Today’s Personal Journal is brought to you by name of advertiser,’” Mr. McQuivey said.

The longer-term threat to the overall media business, however, is the personal intelligent assistant reading publications and creating an entirely new article written for the user. The content served is based on observing the user’s patterns of reading, making that person the only one getting that article.

“Who sponsors that?” Mr. McQuivey asked. “I don’t think there will be a mechanism of easily sponsoring that.”

If the media is disrupted by AI-driven devices and software, then ad agencies are not far behind.

The agency world is already in a state of tumult.

Previously, agencies would get 80 percent of their revenue from traditional ad creation, campaign work and media planning and buying, with the rest from experimentation with other digital platforms and formats and product development. Now the trend is reversed.

“Be a partner with the marketer in building deeper personal relationships,” Mr. McQuivey said. “If advertising as an interruption-based medium dries up, you’ve got to be good at relationships.

“Ad agencies are buying design shops,” he said. “[Technology outsourcing firm] Cognizant bought a design shop. Agencies should be designing relationship experiences to the degree you weren’t before.”

James L. McQuivey is vice president and principal analyst at Forrester Research, and author of "Digital Disruption"

James L. McQuivey is vice president and principal analyst at Forrester Research, and author of "Digital Disruption"

Search and rescue

Any discussion on advertising’s future is remiss without mentioning the two biggest recipients of online and mobile ad budgets: social network Facebook and search engine Google. Both have played a key role in defenestrating media while promising audience reach.

Neither the reach nor the ad dollars from these online giants seems to have paid off for media brands. And ad agencies, guilty in diverting their clients’ budgets, have taken note.

But now the tables may be turning on Google and Facebook as interruption-based advertising enters its swansong period. They certainly are not sitting on the sidelines.

“I think Google and Facebook are just as interested in making the shift to relationships because they can see the same future coming,” Mr. McQuivey said. “But, ironically, they have to disrupt themselves to make the shift.

“If I’m Google, I’d pursue their Google Home effort, but I have to find ways to make it more relevant during the day just as it is with [Amazon’s] Alexa,” he said. “But there won’t be a way to pay for that.”

Digital creates unprecedented relationship potential. Graphic credit: Forrester Research

Digital creates unprecedented relationship potential. Graphic credit: Forrester Research

In a way, just as with the advent of the Internet and the resultant free access to news in the early dot-com years, the tech world seems to be gravitating toward free. Those services are not really free, though.

“All these things that are free, we’re paying AT&T, Verizon and Comcast,” Mr. McQuivey said. “I think what happens, someone like Google wakes up and says we have to get some of the connectivity revenue. So between advertising and connectivity fees, you need to invest more in relationship tools.”

Which makes observers wonder why the likes of Apple and Google that regularly throw up tens of billions of dollars in spare cash and park them overseas do not make a play for the connectivity pipeline.

Whatever the merits, for example, these two companies could have made a serious bid for Sprint or T-Mobile – both second-tier wireless carriers to Verizon and AT&T – when they were up for grabs.

WHILE THE ENTIRE ecosystem is grappling with the onset of AI, augmented reality and virtual reality, the overall advertising environment will not change much by 2020, but the thinking behind it will have matured. That is what Mr. McQuivey anticipates will happen.

“One specific thing is that more advertisers, publishers and vendors will try to explicitly track customers across advertising exposures so that they can know what kind of relationship advertising is contributing to building,” Mr. McQuivey said.

What is his advice to advertisers?

“Start working on your customer database,” Mr. McQuivey said. “Do you have one, and just one? Does it give you accurate and ongoing information about the depths of relationships that you are building today, because none of the relationship tools of the future will help you if you can’t keep track of the relationship you’re building?

“Advertising will persist,” he said, “but it’ll become a means to a bigger end, which is a relationship.”