Scoring 19 out of 100 on average, supply chain transparency remains a rampant issue across the luxury fashion players studied. Image credit: BHRRC

Scoring 19 out of 100 on average, supply chain transparency remains a rampant issue across the luxury fashion players studied. Image credit: BHRRC

International nonprofit Business & Human Rights Resource Centre (BHRRC) is out with new research.

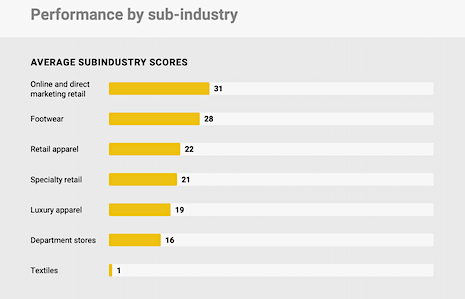

According to the fourth edition of the KnowTheChain Apparel & Footwear Benchmark, several brands are falling behind in the fight against forced labor, despite promoting sustainability and social justice progress. Scoring 19 out of 100 on average, supply chain transparency remains a rampant issue across the luxury fashion players studied.

“While the largest apparel companies have experienced staggering revenue growth and profit margins since the pandemic, those who work for them continue to face some of the most impoverished conditions,” said Áine Clarke, head of KnowTheChain and investor strategy at BHRRC, in a statement.

“The largest apparel companies have experienced a combined growth of $42 billion since 2022, yet an estimated $71 million is still owed to workers because of wage and severance theft committed during the pandemic,” Ms. Clarke said. “This disparity is most evident in luxury fashion, where record revenue growth and profit margins seem increasingly divorced from workers, and working conditions, in global supply chains.

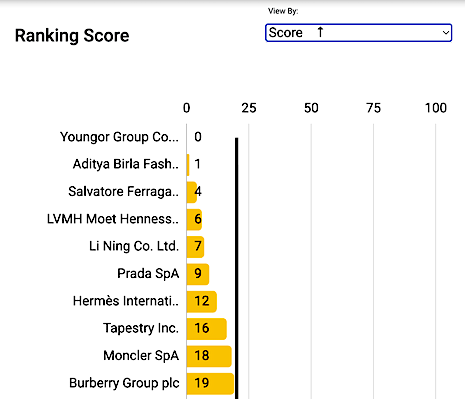

“For multiple years running, luxury brands such as LVMH (6/100) and Salvatore Ferragamo (4/100) have performed among the poorest in the benchmark.”

Assessing 65 of the biggest apparel and footwear companies in the world, benchmark criteria is based on the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and covers due diligence, policy commitments and remedies. The report's methodology uses the ILO core labor standards, which represent working rights the organization has pegged fundamental, including freedom of association, the right to collective bargaining and the elimination of forced labor, child labor and discrimination — all standards were developed with the advising of stakeholders and upon review of external benchmarks, frameworks and guidelines such as the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct.

Luxury lags behind

KnowTheChain, a program of BHRRC focusing on forced labor rights issues within global supply chains, publicly assesses companies against three high-risk segments: apparel and footwear, food and beverage and information communications and technology.

While the average score for all brands listed throughout the report landed at just 21 on a scale of 100, the vast majority of luxury apparel performances ranked poorly, receiving an average subindustry score of 19 out of 100.

High-end fashion labels have been platforming conservation efforts, hosting equity-oriented events and partnering with third-party nonprofits, though based on this data, the sector is failing to eradicate forced labor.

Luxury brands are falling behind in the fight against forced labor. Image credit: BHRRC

Luxury brands are falling behind in the fight against forced labor. Image credit: BHRRC

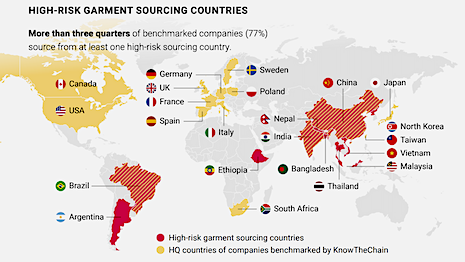

Findings reflect that workers in countries including Argentina, Bangladesh, Brazil, China, Ethiopia, India, Malaysia, Nepal, North Korea, Thailand and Vietnam are the least safe.

Of all benchmarked companies, 77 percent source from at least one of many nations that the report shares is battling heightened risk. More than half of luxury brands have stated that they source from a minimum of one of the aforementioned regions, and only 8 percent disclosed information or details about forced labor risks found across supply chain tiers.

In luxury, just seven out of 20 companies produced a full first-tier supplier database with names and addresses, including Italian fashion house Prada, which only partially revealed one. All of the 25 luxury operations listed failed to provide this information for its second or third tier.

The only brands that were able to reveal sourcing countries of raw materials were French luxury conglomerate Kering (see story) and French fashion and leather goods house Hermès (see story).

Most of the fashion companies included in the study are sourcing from high-risk nations for forced labor. Image credit: BHRRC

Most of the fashion companies included in the study are sourcing from high-risk nations for forced labor. Image credit: BHRRC

Allegations of forced labor were identified in almost half of all companies, while 20 percent of entrants scored a five out of 100 or lower on the ranking. Thirty-four percent achieved a score of less than 10.

Seven out of 20 premium fashion names did not provide any information on how they perform human rights risk assessments in supply chains, while four out of 20 reported “limited information.”

Brands scored the worst on purchasing practices, themes and remedies. As for the latter, only 22 percent of companies provided an example of outcomes for workers.

Just 11 out of 100 high-end houses provide access to solutions to supply chain laborers and representatives. Not a single prestige company disclosed taking steps to analyze the impact of its purchasing practices, which cover procedures related to pricing and order placement timing, as well as supply chain working conditions and responsible buying.

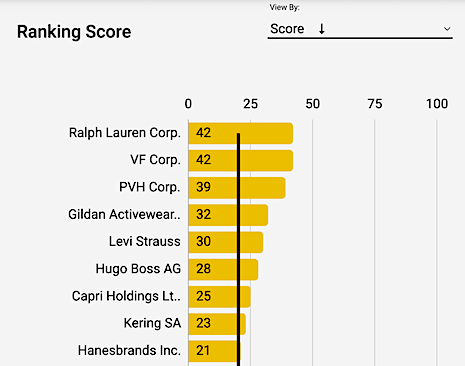

Brands such as Ralph Lauren, Hugo Boss and conglomerates including Kering rank above their luxury peers. Image credit: BHRRC

Brands such as Ralph Lauren, Hugo Boss and conglomerates including Kering rank above their luxury peers. Image credit: BHRRC

Recruitment, a key piece of protecting migrant workers, is an area that likewise lands toward the bottom performance-wise, with businesses receiving an average score of 14 out of 100 for their efforts.

Twenty-two percent of organizations disclosed that they engage with unions to better the freedom of association in supply chains, a provision KnowTheChain considers critical to preventing abuses. Luxury did much worse in this regard, achieving a tally of eight out of 100.

With the production cycles picking up in luxury to match the pace of the entire fashion industry, pressure is mounting in workshops and at production facilities worldwide.

“The fashion industry has long since been in the media spotlight for its endemic human rights risks and labor abuse scandals,” said Ms. Clarke, in a statement.

“Despite this, most companies are not adapting to the scale and scope of these issues across global supply chains,” she said. “Exacerbated by multiple crises in 2023 — including climate breakdown, international conflict and post-pandemic realignment — alongside an increase in strategic litigation, legislation and associated operational, reputational and financial risks, makes this ‘business-as-usual’ approach by so many brands shortsighted and misguided.

“With the recent political deal on the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive, this year’s benchmark findings should serve as an especially timely call to action for companies and their investors to look again at business models that perpetuate abuse and create shared prosperity for CEOs, shareholders and, crucially, workers alike.”

False security

While fast fashion has been long under fire for its unjust working conditions and environmental destruction, luxury oftentimes escapes similar volumes of criticism.

Allegations have been mounting in recent years, however. Unauthorized subcontracting, forced overtime, lack of safety, union busting and exploitation are all topics being broached by social justice advocates.

According to the benchmark, investigations suggest that luxury companies may be using many of the same practices as fast fashion, driving down order price payments and putting extra pressure on exporters to bring in items at quicker and cheaper rates.

Forces incentivizing luxury players to “do good” surely exist, and are drawing attention, as nonprofits such as BHRRC bring behind-the-curtain activities to the forefront. Experts point to the fact that strong ESG strategies have been proven effective in garnering loyalty from consumers (see story).

Luxury houses such as Ferragamo, Prada and Burberry are ranked lowest for forced labor infractions in fashion. Image credit: BHRRC

Luxury houses such as Ferragamo, Prada and Burberry are ranked lowest for forced labor infractions in fashion. Image credit: BHRRC

Additionally, as climate change continues to wreak havoc on supply chains and cause disruptions, fashion will continue to be impacted (see story). Related legislative updates are impending, adding a layer of urgency (see story).

Research exercises are providing sobering windows into the future of fashion as the year 2030 (see story) nears.