Tuesday's decision, which ruled in favor of Chanel, sparks questions as to how a legal victory against one consignor may impact other high-end resale players. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around

Tuesday's decision, which ruled in favor of Chanel, sparks questions as to how a legal victory against one consignor may impact other high-end resale players. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around

The latest chapter of a legal battle involving French fashion house Chanel reached its conclusion earlier this week.

Winning its lawsuit against popular luxury reseller What Goes Around Comes Around (WGACA), experts are weighing in on how the victory may impact other resale players. Analyzing Chanel’s approach to thwarting the use of its name and likeness on secondhand platforms could help clue audiences in on how the move informs the market’s future.

“I think this case will help us narrow the definition of both fair use and vintage and provide guidance to resellers such as WGACA and The RealReal about the extent to which they are able to resell products,” said Rania Sedhom, founder and managing partner of Sedhom Law Group, New York.

Ms. Sedhom is not affiliated with Chanel, but agreed to comment as an industry expert.

Chanel, Inc. v. WGACA, LLC

The United States District Court for the Southern District of New York’s judgment is rooted in allegations that WGACA misused Chanel’s brand without proper authorization.

Examples cited included the reseller's promotion of discount codes including “COCO10” and social media hashtags such as “#WGACACHANEL.”

The judgment is rooted in allegations that WGACA intentionally misused Chanel’s brand without authorization. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around

The judgment is rooted in allegations that WGACA intentionally misused Chanel’s brand without authorization. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around

Lawyers say the moves carried the potential to confuse buyers on the nature of what was, in actuality, a nonexistent business relationship between the prosecuting party and defendant. The brand also stated that it had previously refused a partnership with WGACA.

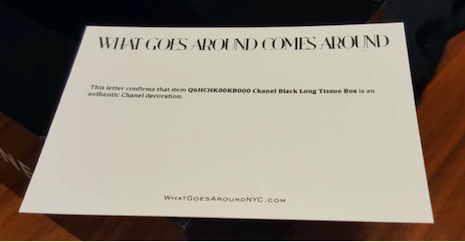

The concern is one of perception: Chanel argued that messaging alluding to a connection between the pair may have worked to falsely credential apparel and accessories that, in certain cases, are alleged to have not met WGACA’s 100 percent authenticity guarantee.

“While the [items WGACA sold were] ‘authenticated,’ it is unclear how and by who,” Ms. Sedhom said.

“Typically, the only true authenticators work for the brand.”

Seeking compensatory resolve, complaints additionally pointed to the alleged sale of counterfeit handbags on WGACA's behalf (see story).

A Letter of Authenticity from WGACA for Chanel vintage product. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around

A Letter of Authenticity from WGACA for Chanel vintage product. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around

“Chanel sued WGACA and alleged four causes of action: trademark infringement, false association, unfair competition and the sale of counterfeit goods, including Chanel,” Ms. Sedhom said.

“Chanel, for example, alleged that WGACA sold counterfeit goods that bore Chanel’s trademark and stolen serial numbers,” she said. “It also alleges that WGACA’s use of Chanel’s trademark in marketing and on its website suggests a brand affiliation that is false.

“In other words, Chanel did not license its trademark to WGACA like it does with department stores who are authorized to sell its handbags, wallets and other items.”

WGACA negates these claims, expressing disappointment with Tuesday's verdict after jurors presiding over the case, initially filed in 2018, delivered a decision that ruled in favor of Chanel on all counts.

“WGACA argues that it is using Chanel’s trademarks fairly and its use of the trademark is solely to identify the product and does not indicate an affiliation,” Ms. Sedhom said.

“WGACA affirmed that it sells authentic vintage and does not have counterfeit products for sale.”

The outcome will cost the defendant $4 million in damages, placing the industry on high alert.

In the aftermath of recent events, however, some question whether the result will move the needle all that much.

On Feb. 6, the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York ruled in favor of Chanel on all counts. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around

On Feb. 6, the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York ruled in favor of Chanel on all counts. Image credit: What Goes Around Comes Around

On the communications front, merchants may consider exercising more care across their digital channels, though this would not be the first court proceeding to influence how fair marketing practices unfold (see story).

What is more, regardless of fault, the case outcome could lead resale operators to expand transparency mechanisms, in order to offset risk on the product side.

The prioritization of strong in-house authentication processes, tightening of listing reviews and establishment of traceability efforts (see story) have also been in motion for some time (see story).

“The law hasn’t changed in this regard — the selling of counterfeit merchandise is illegal,” Ms. Sedhom said.

“At a minimum, resale sites will have to reimburse duped consumers,” she said. “If counterfeits are prevalent, resellers should expect to be shut down entirely.”

Smart strategies and savvy consumers

By and large, luxury views the lack of control it has over how its products show up secondhand as a challenge.

Besides the inability to profit directly from these iterative sales, designer items on these sites are oftentimes past-season and preloved, neither of which aid the sale of new collections.

Otherwise, variances in branding, as well as markdowns and the manner in which products are merchandised, are among a list of realities that have irked high-end entities. Legacy brands have no say in where their goods are presented, what their apparel and accessories are placed next to, or how high or low price points are set.

These elements, they argue, enhance or erode current market values, consequently affecting desirability, though ubiquitous adoption, especially on behalf of younger shoppers, has forced steady acceptance in the space.

“Many brands shy away from aspirational consumers who want to purchase secondhand goods at a discounted price,” Ms. Sedhom said.

The resale value of Chanel's bags continues to skyrocket. Image credit: Shutterstock

The resale value of Chanel's bags continues to skyrocket. Image credit: Shutterstock

Some heritage brands are friendlier with third-party players than others, even reaching across the aisle to partner with, say, a Vestiaire Collective, as was the choice of British fashion label Burberry last year (see story). Others are folding these divisions into their businesses, exchanging the labor of managing logistics for the benefits of end-to-end oversight of appearance, pricing and quality control (see story).

Italian fashion label Valentino (see story) and French fashion house Balenciaga (see story) offer two fairly topical case studies. Chanel’s story looks slightly different.

The luxury leader is notoriously strict when it comes to distribution. Its ability to ensure mainline demand remains high has created an environment where the resale value of its bags continues to skyrocket.

Styles such as the Classic Flap are increasingly garnering consignors who choose to trade their handbags for cash average annual returns that are on par with or greater than the S&P 500.

By many measures, Chanel's stringent retail and wholesale strategies support the bottom lines of the very enterprises it opposes in determining that its image is worth protection.

Chanel's intertwined “C's” and clean, customized typeface are viewed as hallmarks of luxury and elegance. Image credit: Chanel

Chanel's intertwined “C's” and clean, customized typeface are viewed as hallmarks of luxury and elegance. Image credit: Chanel

WGACA, which has since inked a deal with online marketplace eBay (see story), is not the only actor Chanel has flagged to date. A separate suit against luxury resale platform The RealReal, which has come under fire for similar allegations in recent years (see story), is ongoing.

Based on the state of current verdicts, and the status of those to come, it is possible that WGACA, The RealReal and others are held liable for infringements more frequently. Moreover, the added pressure could trigger a wave of counterfeit crackdowns.

Litigation, however troublesome, has been known to help clarify greyer areas of intellectual property law and fair use policies. Lastly, lest fashion forget, consumers are becoming savvier by the day.

Fans of personal luxury goods and mass market shops alike are arguably more determined and incentivized to investigate product quality than ever before. Looking ahead, resale success may rely, in part, upon upping education efforts.

Here, companies like TikTok and Entrupy are exploring cross-industry partnerships as a means of spreading information (see story). The release of campaigns that touch on spotting replicas and take audiences behind the scenes at authentication hubs (see story) represents another path to arming shoppers who fall victim to false purchases, potentially also working to deter those chasing fakes.

“A big issue that isn’t addressed with as much fervor as necessary, at least in my opinion, is the consumer’s acceptance of counterfeit products,” Ms. Sedhom said.